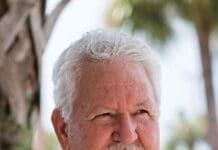

By Sean Dietrich

By Sean Dietrich

Her words were a trip backward on the timeline. Suppers on church grounds, childhoods with calloused feet. Chicken pens, hog roasts, cotton-pickers, fish fries, front porches.

I played music and spoke to a room of white-haired women. It was a dark-lit bar, with decent onion rings and heavy burgers. Ladies from all walks of life held glasses of beer and wine. A few had canes and walkers. Eighty-two-year-old, Jo, approached me first. She wore a white blouse with houndstooth scarf. She asked if she could buy me a beer. I yes-ma’amed her. “Don’t yes-ma’am me, boy,” she said. “I’m trying to hit on you. Ruins the excitement.” We sat at the bar together. She lit a cigarette. “Doctor says I shouldn’t smoke,” said Jo. “But I smoke two a day. One in the morning, one at night.” Jo is an M-80 firecracker. She is from rural Alabama and she sounds like it. She is a writer, a poet, an artist, and a shameless flirt. She told stories, of course. Her words were a trip backward on the timeline. Suppers on church grounds, childhoods with calloused feet. Chicken pens, hog roasts, cotton-pickers, fish fries, front porches. By the time her cigarette was a stub, she was talking about her husband. “I miss him so much,” she said. “He was a precious man, the best thing in my life. You look a little like he did.”

There was another woman. Ella. She was eighty-nine. She asked if the band would play “Tennessee Waltz.” We played it at an easy tempo. She slow-danced with her son. He was careful with her. When he dipped her, she was nineteen again.

Ella’s husband died when she was forty. She never remarried. “Always had me a few boyfriends,” she said. “Seems like I went dancing almost every weekend. My sister would watch my kids, us girls would go out jukin’.” Juking.

Ninety-nine-year-old Mary sat at a table with her eldest daughter. She could only move her feet to the music. Occasionally her head bobbed. “I growed up in the Great Depression,” Mary said. “You ever hear of that?” Once or twice. “They was bad times,” she went on. “My daddy saved chicken bones for fish traps, then he saved fish bones for the chicken feed.” Her mother died when she was fourteen. Mary became maternal head of her family. She could slaughter poultry, rock babies to sleep, and re-screen doors by age sixteen. “I used’a mix ketchup and water for supper,” she said. “Called it tomato soup. Sometimes I made biscuits if we had flour. I kept my family alive. “My brother stole chickens from a farm up the road. If we ever had extra money, I’d tell him, ‘Jeremiah, leave this here dollar on their porch, we ain’t thieves.’ We didn’t WANNA steal, you know. But we had to.” She asked if my band would play “Little Brown Church in the Vale.” We did.

At the end of the night my new friend, Jo, bid me goodbye. She asked if she could show me something. She dug in her pocketbook. She handed me a crinkled black-and-white photo of a young woman holding a baby. A tall man, standing beside her. “That’s me and Tom,” said Jo. “Before he died. Oh, I’s so pretty back then, wasn’t I?” You were, ma’am. But you’re absolutely breathtaking now.