Seldovia, Alaska, sits somewhere near the top of the world. It’s a nanoscopic village on the North Pacific. Population 225. Tons of fishing boats. A lot of cold, icy, Kachemak Bay water.

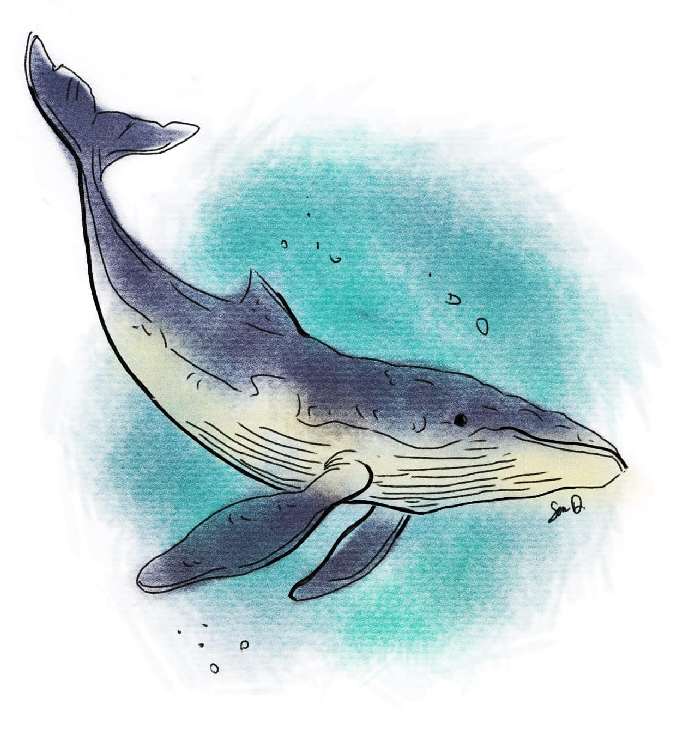

A few days ago, a local spotted something huge stranded on the beach. It was a minke whale. About the same length as a mid-size Toyota.

The whale was struggling. Thrashing around and panting. The whale was fighting to breathe.

The passerby ran for help.

When a live whale finds itself stuck on a beach, you don’t have a lot of time. Maybe 20 minutes, tops.

Dehydration is often what kills the whale. Or the whale might drown because its airway faces the tide. Often, it’s suffocation that kills a stranded whale.

Remember when you were a kid, and you swam in the pool all day? Remember how when you got out of the pool, your whole body felt heavy? That’s because for hours water supported your body weight while all your friends played Marco Polo, thereby traumatizing some unfortunate child so that this child would be receiving therapy for the next, say, 30 or 40 years of his or her respective adulthood. Not that I would know anything about this.

So anyway, after being buoyant all day, your little-kid muscles weren’t used to supporting your weight. Once you got out of the pool, your body felt heavy.

Likewise, whales spend a lifetime in the water. Their bodies are not built to handle their own weight. When a whale lies on the beach, gravity crushes its huge frame, making it almost impossible to breathe.

The whale in Seldovia was gasping, with roughly three tons sitting on its lungs. It was dehydrating in the sun. It wouldn’t be long before the whale would just give up and die.

Each year, about 2,000 whales strand themselves on beaches and die. That number is rising. Nobody really knows why. Even fewer seem to care.

Someone in the village contacted Stephen Payton, the environmental coordinator. In his 10-year career, he had never encountered a live beached whale. He wasn’t sure what to expect when a neighbor offered him a ride on a four-wheeler.

“It was really scratched up,” Payton said. “You could tell it had probably been rolling around on the rocks.”

When he got to the beach, he had likely expected to find a dead whale. What he found, however, was not a deceased cetaceous creature.

When Payton arrived at the shore, there was a crowd of locals who had formed a bucket brigade. They were hauling seawater from the Pacific, using five-gallon buckets, dousing the whale.

The villagers had wrapped the whale in wet towels to protect it from sun exposure. They did not leave the whale’s side. Twenty minutes turned into an hour. One hour turned into six.

After a full day of caring for the animal, the tide arrived. The whale reoriented itself and swam into the water and the crowd cheered.

But the whale did not swim off into the deep. The whale stayed in local waters for days, surfacing frequently, and spouting at local villagers. Like it was saying thank you.

Now think of all the times you honestly believed you weren’t going to make it. Try to remember the individuals who appeared, seemingly out of nowhere, who stood beside you during hard times, even when odds were not in your favor. Remember those people?

Good.

Now go be that person for someone else today.