A small town. The kind of American hamlet that causes you to start looking around for the Norman Rockwell signature. Hanging begonias. Storefronts with colorful awnings. A cute downtown.

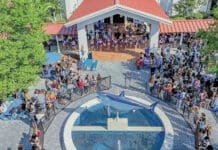

There was a loud party happening on Main Street.

I followed the sound of distant music and many voices. I suddenly realized I was still wearing my pajamas. I shuffled into town barefoot, with sleep crusted in my eyes.

The sun was shining. Birds were cackling. People were everywhere. It was a veritable town-wide hoedown.

I saw women positioning casseroles on card tables. I saw children playing tag. Old men in aprons were deep frying hunks of fish.

There was music playing at the hardware store. Good music. The kind with twin fiddles. People were dancing before a plywood stage. Each front porch was crowded with people drinking lemonade and sugary tea.

Everyone was there, the whole gang. I saw them all. All my loved ones who died and left me behind. All my friends who met untimely ends. All my relatives who were called home too early. All my kin.

They were all right here, holding plates of hot food, mingling with one another. Everybody was smiling, throwing their heads back, laughing until they couldn’t breathe.

I saw grandparents, deceased uncles, departed aunts, and cousins who died before they were old enough to know what life was about.

I saw multitudes of unfamiliar children, dancing while the musicians played “Turkey in the Straw.” I asked an old woman nearby who all these children were.

“Those are the babies who died in the womb,” the woman said. “Aren’t they precious?”

We were interrupted when a large pack of dogs came running through the town, careening up Main Street. They came stampeding like a herd of bison. Among them, I saw six of my own dogs.

I saw Lady, the cocker spaniel who died in my arms when I was a teenager. I saw Joe, who was hit by an SUV in a hit and run. I saw Boone, the collie-mix who died in a veterinary office while gazing into my eyes. I saw Ellie Mae, the bloodhound I’ll never get over.

In a nearby park, I watched old friends play baseball. Mister Reginald was pitching—the retired Methodist minister who once lived on my street.

I saw my grandmother, standing at home plate, holding a hickory bat in her hands. Lord have mercy. She was a teenager, long and beautiful, with raven hair and Hershey’s Kiss eyes.

After the ball game, I was hungry. So I found a paper plate and stood in line at one of the food tables. A guy in line said, “Sean! Don’t you remember me?”

I stared at him, but didn’t recognize his face.

“It’s me!” he finally said. “James!”

“JAMES!” I screamed. James and I were friends as kids. He died driving home from his very first job. He wrecked his car on the interstate. I sat on the front row at his funeral and wept alongside his sisters.

Mid-hug, I saw someone else familiar. She was standing behind a food table, serving people. I knew those two fiery eyes, flecked with tinges of playfulness. It was my mother-in-law.

She was behind a crockpot, wielding a long spoon, wearing an apron that said “KISS ME, I’M METHODIST.”

When she recognized me, she shouted my name and came running around the table to hug me. It was a colossal embrace that made my ribs squeak.

“You have no idea how much we all miss you back home,” I told her.

Next, I saw Aunt Judith, Uncle Tommy Lee, the Williams boy, my old Little League coach, Cousin Elroy, Cousin Rose, Cousin Ray, and dear Mrs. Betty Lamb, who taught me in elementary school. I saw hundreds more familiar faces. Maybe thousands.

Then an old woman grabbed my arm and said, “There’s one more person you need to meet, sweetie.”

he led me to the edge of town, to a meandering river. There, on a shallow wooden bridge sat a young man, feet dangling over the edge, trousers rolled up to his knees. He was holding a long fishing rod like a grown-up version of Huck Finn.

He saw me.

He stood.

My God, he was so young. He was so very young and so very lean. He had a mess of red hair atop his head, and his patent pending matinee smile was unchanged. He was wearing the same shirt he died in.

We embraced and I heard myself say his name. A word I’ve been waiting to use for a long time.

“Daddy.”

I could smell his deodorant, a scent I haven’t known in years. I could feel his lean trunk beneath my arms, and his beating heart only inches from my own.

“What is this wonderful place?” I asked my father.

“Does it matter?” he said

“Yes, it matters. Because I don’t ever want to leave.”

He smiled. “Neither do any of us.”

Then I woke up.

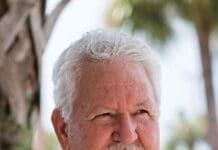

Sean Dietrich is a columnist, novelist and podcast host known for his commentary on life in the American South. His work has appeared in Life Media publications, Newsweek, Reader’s Digest, Southern Living, Garden and Gun and in newspapers from Savannah to San Diego.